The History of Photography in Lebanon from its Beginnings

The invention of photography in the 19th century came at a time of major developments in the Near and Middle East. So it is not out of place here to recall them so that the context of the development of photography in this region may be better understood.

In 1799 the study of Egyptology took a great leap forward thanks to a discovery of great importance. A French officer came across the famous Rosetta Stone, which made possible the deciphering of the hieroglyphics. Although the stone was taken by the British and Thomas Young had begun to decipher it, it was the French historian Jean François Champollion who finally completed the study, in 1822.

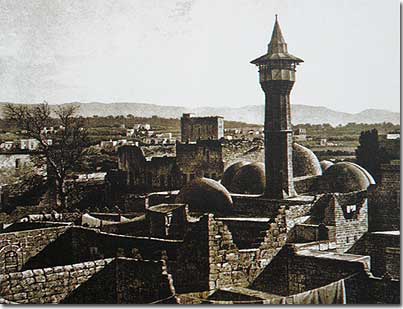

The first photograph taken of Beirut, by Horace Vernet and

Goupil-Fesquet in 1840. In the foreground is the Al Saraya Mosque

In 1812, Petra and Abu Simbel were effectively explored by the Swiss Johan Ludwig Buckhardt.

The first regular shipping line between Marseille and Alexandria started operation in 1835.

In 1859, Ferdinand de Lesseps (1805-1894) began the piercing of the Suez Canal, which entered into service ten years later following an official international ceremony under the patronage of the Empress of France, the Emperor of Austria and the Crown Princes of Prussia and Denmark. So the lines of communication, transport and commerce were greatly shortened.

Jerusalem, which up till then had aroused little interest apart from its Holy Places, developed as an international center. The British were the first to open a consular office there, in 1833, followed by the Prussians in 1842, the French in 1843, the Americans in 1844, the Austrians in 1845, and the Russians in 1858. In 1837 the Turkish postal services began to operate from Palestine and the first telegraphic service in the region was installed in Jerusalem in 1865.

In 1881, the first wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived in Palestine, among them photographers.

During the 19th century, there were two ways of corresponding in the Ottoman Empire. There was the Turkish Post Office, slow and not very reliable, and there were the various post offices opened by the foreign powers. The most efficient ones were that of Austria, backed by Lloyd’s maritime Austriaco, and that of France. It was in this way that the French postal service established itself in the Ottoman Empire from 1830 on. This implantation was basically meant to make up for the shortcomings of the Turkish postal service and to improve the postal communications necessary for the smooth functioning of the French and other European enterprises and commercial operations set up in the main ports around the Mediterranean. Among the first five post offices installed between 1830 and 1849 was that of Beirut, in 1845. The stamps affixed on the letters were those of the countries running the post offices, and the stamped mail was carried regularly by the frigates anchoring off the Grand Hôtel d’Orient (hôtel Bassoul) near the present Hotel Phoenicia.

In the 19th century Britain and France had little difficulty extending their influence over the Levant, for although the Ottomans had been ruling there for three centuries, they had imposed neither their language nor their civilization, and had never imposed their culture over the Near East. What was more, they openly despised the local populations. Consequently, the rule of the countries of Western Europe had much more influence than that of the Ottomans. France spread its influence over Egypt, Lebanon and Syria through its commercial and cultural activities and through its social and cultural services. Great Britain was more concerned with the work of its missionaries and the extension of Protestant influence. One of the principal aims of these missionaries was the conversion of the local populations, the Jews in the Holy Land, particularly in Jerusalem, the Druze in Mount Lebanon, and the Greek Orthodox in Beirut, with financial aid for those who were converted. The limited success they met with in their mission seems today to be a proof of the difficult conditions of survival in the region.

At first, France was more successful in spreading its influence over the area. Britain, being preoccupied by its colonial efforts in India, was less concerned with the Near East. Further, the attitude of the French towards the local peoples proved more agreeable to them than that of the British.

During the second half of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire, called by the Europeans the Sick Man of Europe, was crumbling on every front. This weakening of the Empire was due to several factors.

-As a result of the participation of France together with Great Britain during the Crimean War (1851-1853), Sultan Abdel-Magid was obliged to grant certain privileges to the non-Muslim inhabitants of his empire and to strengthen the reformist current in conformity with European conceptions.

-During the 1870s, the internal situation in Egypt deteriorated. The country was bankrupt and the Panislamic nationalist movements opposed to westernization became more numerous and violent. The condominium established by Paris and London over the finances of the Khedive provoked strong nationalist agitation which led up to the military revolt led by Arabi Pasha in 1882 and on June 11th to the massacre of some sixty Europeans in Alexandria. One month later, the British Navy bombarded Alexandria and then made landings there. In September, the British forces finally sent an expeditionary corps to occupy the whole of Egypt.

-From 1881, in view of the increasing vulnerability of its finances, the Ottoman Empire was obliged to hand over financial control to foreign powers, in particular France and Britain. At this time the European nations began to concern themselves seriously with what was called “the oriental question” when referring to the chaos.

Imperial Ottoman Bank in Beirut - 1906

It was during this time that, despite the grave financial crisis affecting the Ottoman Empire, the Imperial Ottoman Bank was set up on February 4th, 1863. A contract was concluded between the shareholders of the Ottoman Bank, founded in 1856, the Ottoman government, and the British and French investors. Acting both as the State bank and as public treasury, the Imperial Ottoman Bank presented itself as a commercial bank, so consolidating its relations with the market thanks to its network of branches, the most important of which was the one in Beirut. The 18th February, 1875 was a key date for the future of the Bank, since it was then that by an agreement ratified by an imperial firman the government extended its prerogatives by confiding to it control of the State budget and the improvement of the financial situation of the Empire. The function of State Bank for the Imperial Ottoman Bank was thus clearly reaffirmed. The Bank was entrusted with the indirect taxation and with the salt and tobacco monopolies, so increasing its commercial activity and developing a twofold activity of financing the Turkish economy and encouraging enterprises. It was in this way that in 1888 the Bank was behind the creation of the Port of Beirut. In association with partners it was concerned in the Beirut-Damascus Railway (1892), later in 1900 extended to Homs, Hamah and Aleppo. It supported several railway projects and also shared in several mining undertakings.

Inauguration in 1903 of the railway station at the

Port of Beirut, decorated with Ottoman flags

So, during the 19th century, a period of torment, just when photography was spreading over Europe, this part of the world was undergoing radical change.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833), an inventor of Chalon-sur-Saône, was in 1826 or 1827 the first to fix images of acceptable quality on tin plates covered with Judea bitumen, a sort of tar that had the property of hardening when exposed to light.. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce died in 1833 and Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) carried on with the improvement of the procedure. By discovering the principle of the latent image, Daguerre found a way of shortening the time of exposure to a few dozen minutes. In 1839 he took his invention to the learned parliamentary deputy François, who lent him his support. Thus the invention of photography dates officially from 1839, the year when Arago officially presented to the Academy of Sciences the “invention” of Daguerre, Daguerrotype. By this means of producing an image on a plate of silvered copper, it was possible to produce a photograph after an exposure of “only” half an hour. William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) was at that time conducting research parallel to that of Niépce and Daguerre, begun in 1833. In 1860 he invented the “caloatype” or “collodion”, a process of negative and positive allowing a number of copies of images to be produced.

From then on, drawings lost much of their use for documenting information, being replaced by this printed image. The well organized bodies of painters, lithographers and engravers who came to the sites to make illustrations of places and landscapes were overwhelmed and immediately realized the important consequences implication of this discovery.

While in Europe the development of photography was opposed by no doubts about it, in the Ottoman Empire it ran up against the hostility of conservative religious circles who rejected any pictorial representation, considering it contrary to the principles of Islam. In point of fact, when the Turks took Constantinople, the Koran has fiercely condemned idolatry in Surat 16, “Serve God and abandon idols.” Consequently in regions under Islamic influence one found no portraits, no outlines of animals or of whatever possessed an immortal soul. Everything dating from the Byzantine period had to disappear. Fortunately, something has remained, such as the mosaics in the mosque formerly the Holy Wisdom church in Istanbul, which were simply covered with plaster rather than being destroyed once and for all.

But as the Empire gradually became modernized under the pressure of the European powers, photography became generally accepted. This modernization of the Empire had already started thanks to Sultan Mahmoud II (1808-1839), who showed a lively interest in European technical inventions. He turned to European experts to reorganize his administration and his army and even authorized the creation of theatrical groups and orchestras. This ability to break with tradition was shown clearly in 1837 by the showing to the public of his portrait executed in oils. In the same years medals were struck with his effigy to be offered to distinguished guests and to various dignitaries. So it was that in1847 the musician Franz Liszt received one of these medals on the occasion of a concert given in the Palace. It then became usual to put up portraits of important people and members of one’s family in the offices of government buildings, following the example of the Sultan, without provoking the least reaction from the public. The art of making family portraits spread over all the provinces of the Ottoman Empire, particularly Mount Lebanon, these becoming current among the important personalities and what was then the bourgeoisie. The art of portraiture became established in the 19th century and it became common for notables to have their portraits painted by Italian or Russian artists. Portraits of ancestors and later of younger family members were often hung up in the reception rooms of large houses.

The Ottoman court was by no means indifferent to the advantages for illustration and propaganda offered by photography. Early after the invention of photography the sultans surrounded themselves with photographers chosen from among the best, generally Christians, but above all members of the Armenian community. The latter really made a great contribution to the development of the arts, crafts and new techniques in the Ottoman Empire. Being unprejudiced against the representation of individuals, members of the Armenian community were widely chosen to be the portraitists of the Empire and they had a near-monopoly of studio photography. Armenian photographers had students in all the principal towns of the Ottoman Empire, the most reputed being Garabedian and Krikorian at Jerusalem, Guiragossian and Sarrafian at Beirut, Berberian at Amman, Halladjian at Haifa and the three brothers Horsep, Viken and Kevork Abdallah at Istanbul. The last-named stood out as among the most illustrious photographers of the first generation. Turks of Armenian origin, the young brothers were early on introduced into the artistic milieu. Kevork (1839-1918) studied art at the Murad Ruphaellian School at Venice, where the children of upper class Armenian families were traditionally sent. Vichen (1820-1920), a painter noted for his miniatures on ivory and mother-of-pearl, worked at the court of the Sultan. After being assistants of the German photographer and chemist Rabagh in the Pera district of Istanbul, the three Atallah brothers decided to purchase his studio in 1858, when Rabagh expressed a desire to go back to Germany.

Thanks to the rapid evolution of the techniques of photography, particularly that of the collodion negative, which allowed negatives to be obtained on glass plates and several copies to be printed from one negative, the picture industry developed rapidly during the eighteen-sixties. The Abdallah brothers made no bones about dropping daguerrotype in favor of the new technique. As even this did not give them entire satisfaction, they decided to go to the Centre Mondial de la Photographie in Paris in order to learn about the latest innovations from such eminent photographers as Count Agnado and Baron Taylor.

Once back in Istanbul, they were introduced to Sultan Abdul Aziz by the intermediary of the Ambassador of France, Marquess Moustier. The brothers very soon gained the favor of the Sultan and became his official photographers. They were then charged with various missions, including a photographic campaign covering all the provinces of the Ottoman Empire, and they also took part in different exhibitions in Europe, among them the Exposition universelle in Paris in 1878.

The photographs taken by the brothers Abdallah allowed the Sultan to send to Western countries a modern image of the Ottoman Empire. Thus it was that European monarchs visiting Istanbul received portraits painted on ivory and also photographs showing buildings, the sumptuous life at the Imperial Court, and modern achievements such as schools, hospitals, weapons, the Ottoman Navy and streets that were paved and lit up at night. Further, these photographs allowed the Sultan to be known throughout the four corners of his immense empire, although he himself left his palace only on the rarest occasions.

The Abdallah brothers were also called on by members of the European royal families, such as Prince Albert Edward of Great Britain and his wife, Emperor Napoleon III of France, and even Emperor Franz-Joseph of Austria, who wished to have his portrait taken when he was visiting Istanbul.

In 1886, the Abdallah brothers settled in Cairo, where they opened a branch which prospered until 1895, thanks to the support of the khedive Tawfiq.

The Abdallah brothers were the official photographers of the Sultan for the portraits of the most important personalities of the time. They were called on to immortalize for posterity official and family events and important occasion in the history of the Ottoman Empire. The abundance of their output in public and private collections bears witness to their commercial success.

The technical progress in photography, especially the reduction of the time needed for the exposure and the appearance of snapshots, allowed from 1880 onwards the reduction of the weight of the equipment and the widening of the activities of photographers with more and more scenes taken outside the studios. With the discovery of how to make celluloid, the first artificial plastic material, and the marketing of the Kodak cameras with the slogan at that time famous of “You press the button, we do the rest”, the art of the photographer was greatly speeded up. Used in the place of the sensitive glass plates, which were difficult to prepare and especially to carry about, the flat dry rolls henceforth allowed a large number of photographs to be taken in only a little time.

The Sarrafian brothers were the first to make full use of this great technological advance. They were particularly interested in subjects taken from daily life, ones that they preserved for the future, the crafts, the coffee shops and musicians, with scenes from town and country which today constitute a unique documentation.

The Armenians therefore were the pioneers and principal actors in the history of photography in the Orient. Following the translation of the book of Daguerre into Turkish in 1841, the Armenian photographs played a constructive role in the Middle East and transmitted a chronicle of Ottoman society in the 19th century. While the Western roving photographers took photographs mostly of the archeological remains and biblical sites, the resident photographers took views in their studios or in the populated districts of the big towns. The intense dynamism of the Armenian photographers continued after the break-up of the Empire in 1918. But their worsened political situation and the massacres of which they had been victims led many of them to go elsewhere, and to take the photographic and technical experience to countries of the Near East such as Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and even Iran, where they found safety.

Lebanon is closely bound up with the history of photography. In fact the first daguerrotype known in the world, showing Roman ruins, was made at the Baalbek site during a photographic expedition led by Joly de Lobnière in 1839. At the same time, that is to say a few months after the discovery of the daguerrotype procedure, another expedition led by Horace Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet took the road to Egypt and Jerusalem and took daguerrotypes of the countries. Among these views there is the first one ever taken of Beirut. The album of this expedition, the Excursion daguerrienne, showing some of the most remarkable views and monuments to be seen in the world, was the project of the optician Le Rebours, and was published in 1842.

While the technology of photography was developing fast during the first half of the 19th century, Lebanon suffered many tragedies and historic upheavals.

In 1805, Muhammad Ali proclaimed himself Pasha of Egypt and set about the difficult task of modernizing his country. He ruled the country with an iron hand and so there were several periods marked politically by uprisings. There was for example the massacre of the Mamelukes in 1811, an event which later inspired a number of orientalist painters. His ambitions took him even to invading Mecca in 1813 and later between 1822 and 1829 to playing a role in the Greek war of independence. In 1831 he conquered Mount Lebanon. Bashir II, emir of the central province of Mount Lebanon and allied to the viceroy of Egypt, advised him to occupy the Lebanese coastal towns without any delay, for he himself had the secret personal aim of throwing off the Ottoman yoke. The Egyptian occupation of Mount Lebanon terminated at the end of the year 1940. Muhammad Ali had to beat a retreat back to Egypt under the joint pressures of the British and the Ottomans, added to the uprising of the local population of Mount Lebanon under their traditional leadership; this population was exasperated by the Egyptian administration’s demand for work without financial compensation, its imposition of forced labor, its measures of taxation and its efforts to disarm the inhabitants. The regime of the double qaimaqamate, Druze and Maronite, was then adopted for Lebanon, but this ran into serious difficulties from the very beginning. Admittedly, the year 1840 saw the end of the Emirate, but it saw also the beginning of an insurrection and of a period of serious trouble, culminating in the massacre of the Christians of Lebanon provoked by the Wali (governor) of Damascus despite the fierce resistance led by the three principal chiefs, Youssef Bey Karam in North Lebanon, Youssef el-Shantiry in the Metn, and Abu Samra Ghanem at Jezzine. These hostilities first broke out in Syria, particularly Damascus, in 1860. Some 20,000 Christians fell victims to the slaughter. The massacres continued in Lebanon throughout the months of June and July until the Ottomans made up their mind to intervene. Finally, under international pressure, Khurshid Pasha convoked the Christian and Druze chiefs to a meeting in Beirut and made them peace proposals which were immediately accepted, both sides agreeing to forget the past.

Youssef el-Shantiry with his weapons

These dramatic events of 1860 led to the arrival of a French expeditionary corps in Beirut and the Shouf. Having become submitted to international law, Lebanon was the official subject of diplomatic conferences. From now on, its destiny was legally no longer under the exclusive authority of the Sultan at Constantinople.

An international commission representing Great Britain, France, Austria, Russia, Prussia and the Ottoman Empire was set up in Beirut, which held a first session on 5th October, 1860 in order to calm the situation, fix responsibility for the conflict, and evaluate the indemnities to be paid to the victims. The commission wished to use the occasion to profoundly modify the administrative organization of the Mountain. After eight months of unceasing efforts, deep divergences appeared between the three most influential members of the commission. Throughout the whole conference, the representative of France, Bêchard, continually urged the interests of Lebanon with greater autonomy and wider territory, while the representative of the Sublime Porte, Fouad Pasha, and the British representative, Lord Dufferin, opposed the French concerns. The representative of Austria, Russia and Prussia played a conciliatory role. Finally on 9th June, 1861 an Organic Statue for the Lebanon on which the members of the Beirut commission had agreed was signed. This Statute, known as the Organic Settlement, made Lebanon an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire with guarantees from the six signatory Powers. In 1867, Italy adhered to the Statute as a seventh guarantor.

Napoleon III of France then considered that the mission given the expeditionary corps was terminated and withdrew his troops from Lebanon. The French government obtained the insertion of an import clause in the Organic Settlement prohibiting the Ottoman authority access to Lebanese territory. So under the regime in force after 1861, a Christian governor directly under the Sublime Porte was nominated. The nomination of the local qaimaqams (local governors), the application of the Organic Settlement and the amendment of its dispositions depended henceforth from the seven Powers. With this regime of independence, Lebanon was cut down and confessionalism established; each of the seven administrative districts was to be governed by a qaimaqam belonging to the religious confession of the local majority – a Maronite for Batroun, Kesrouan, Metn and Jezzine, a Greek Orthodox for Koura, a Greek Catholic for Zahleh and a Druze for the Shouf. The Court of Appeal was to be under the direction of a Druze, political affairs under a Greek Orthodox and a Muslim, and the Bureau under a Turk. This repartition extended even to the minor functions and so confessionalism was destined to long dominate the future of Lebanon, preventing even in our own day the institution of a true civil law society, for it imposed religious marriage and a confessional distribution of ministers, members of parliament, army functions and public administration.

Undoubtedly Lebanon remained unable to prosper economically following the events described above. However, a number of factors converged at this time to favor the development of Beirut and Mount Lebanon. Once the Egyptian occupation was ended, the Port of Beirut became the principal port of the region and measures were taken to improve the infrastructure and to centralize the administrative bodies. For the first time the people of Beirut could participate directly in the running of their city, by means of a municipal council as in Europe and as introduced into Egypt by the French occupation under Bonaparte; the streets were paved, the quays and the depots enlarged, and a quarantine service set up.

Further, the second half of the nineteenth century, a period of expansion and massive industrialization, was one of the most prosperous periods for Mount Lebanon thanks to silk production.

The European textile industry, especially that of silk, underwent exceptional development in the second half of the nineteenth century. So it was under the impulsion of the constant needs of French industry, particularly silk, that the production of silk thread experienced growth in Lebanon.

Mount Lebanon offered the ideal climatic conditions for mulberry trees and the raising of silkworms. The hand labor was skilled and cheap, Christian in the main (about ten thousand workers with an overwhelming majority of women), for it was not the custom for Muslim women to work in the factories.

There were two hundred shops producing silk thread in Lebanon, mostly run by the French. They belonged to prodigious families of the European silk industry, Mourgue d’Algue, Eynard or la Veuve Guérin. The local Akl Shedid, Youssef Tohmeh and Assaad Toubia for their part were among the best reputed.

With the dawn of the nineteen-hundreds, the growing of mulberry trees began to decline because of the competition of the Far East on the silk market. The mulberry trees were replaced by citrus on the coast and by tobacco, vines and fruit trees in the mountainous regions.

Travel then took on a very particular symbolic aspect, with the search for truth, immortality and spirituality.

With the increasing European colonial expansion at this time, there was growing intellectual, artistic and scientific interest in exotic distant locations, the countries of the Near East included. Even if to begin with only the aristocracy could afford such a costly adventure, the Prince of Wales and Count Chambord and their courts traveling much in this region, a voyage in the direction of the East was fast becoming the fashion.

Little by little the enlarged Port of Beirut received more and more ships, the region became more sought-after, and there was a development of organized tours towards the Near East. These expeditions run by Thomas Cook allowed the East to be opened up to a new class of travelers. However, such enthusiasm was of short duration; ten or twenty years later the trip to the Orient had already lost much of its attraction. The “serious” traveler began to complain about the “noisy parties” and their “revolting attitude”. Towards the end of the century, Pierre Loti could rave when recalling his visit to Jerusalem:

“Two other convoys arrived full of those tourists on ‘organized trips’ the men in cheap hats, fat women in bucket hats with green veils... Oh! their manners, their cries, their bursts of laughter in these Holy Places where one normally arrived with humility and recollection when walking in the footsteps of the prophets!”

The tourists traveling on Cook’s Tours were laughingly called “Cooks and Cookesses”, while the locals began to refer to them as “Kukkiyeh”. However, not all were against these Cook’s Tours, and Dame Isabel Burton, who then was living in Beirut, noted in 1871 that “...one cannot speak sufficiently well of Mr. Cook and his institution. It allows thousands who would never otherwise have the opportunity to take advantage of the education derived from travel.”

For the European of the eighteen-sixties, the voyage to the East had become a middle class initiation rite through which a twofold purpose was achieved: a knowledge of the region, with a visit to such legendary cities as Baghdad, and the rediscovery of a lost heritage and a return to one’s cultural sources. The roots of the religions and the civilization of the Western World were closely connected with many places in the East whose names, such as that of Jerusalem, shone with a gleaming aura.

The nineteenth century saw the East through images of a magical and symbolic character drawn largely from the literature of the period. Every place represented (and even now represents) something deeply moving for Westerners. In 1852, Bridges cited Dr. Samuel Johnson in a short paragraph which sums up perfectly the attraction exercised by the Levant over the West:

“The purpose of the voyage is to see the shores of the Mediterranean. On these shores there prospered the four greatest empires of the world – Assyrian, Persian, Greek and Roman. All our religions, almost all our laws, almost all our arts, almost everything that separates us from savages, came to us from the coasts of the Mediterranean.”

When the maritime line between Marseille and Alexandria was established in 1835, large numbers of travelers began to sail across the Mediterranean to the East. At that time several Frenchmen occupied important positions in Egypt, the engineer Linant de Bellefonds, for example, was Director of Public Works and the archeologist Auguste Mariette became Director of Antiquities and founded the Boulad Museum of Archeology in Cairo.

Most places in the East had a quasi-magical attraction for Europeans. The biblical and religious importance of such sites as Jerusalem, Nazareth, Jericho, Jordan and also Mount Sinai aroused deep emotions expressed in the writings of the nineteenth-century authors. Perhaps this may be better understood from the preface written by W.H. Barlett in his book Forty Days in the Desert:

“It is said that he who has drunk of the waters of the Nile will know no peace until he tastes them again... The East must for ever remain the land of the imagination, for it is the cradle of the history of art, of science and of poetry, the cradle of our religion... Our feet follow for ever in the footsteps of the sages, the poets, the prophets and the apostles, or of Him who is greater than them all.”

In ever greater numbers came the travelers who landed at Beirut on their way to Jerusalem or Egypt, and who stopped at certain points such as Baalbek, Tyre and Sidon, turning sometimes aside for a halt in the monasteries up in the mountains.

The second half of the nineteenth century was the period of greatest activity for the development of the city of Beirut.

It is only right to recall certain events which contributed to the expansion of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, namely the development of silk production in Mount Lebanon, the sale of bales of silk from the workshops in Lebanon and sold to Lyon in France, the construction of the route Beirut-Damascus confided to Count Perthuis, the laying down of the railway, and the enlargement of the Port of Beirut. In addition journalism, printing and publication developed steadily.

In 1885 the Mutassarif of Beirut, in agreement with the Municipality, decided to to build a new seray (government house) outside the walls of the old city and to install a public garden in the center of the Burj, which became a most attractive site with a bandstand. The buildings around it were put up in conformity with the principles of town planning, taking into consideration the esthetic aspect, the views and the circulation of the horse-cabs.

All around, edifices of two or three stories were put up. They followed a careful architectural style harmoniously blending European and local forms. It was in this area that the offices of public administration, of the gendarmerie, of the Water Company, the Railway and the Ottoman Bank were installed.

The demand for the construction of hotels increased, with all that implied in the way of cafés, bars and restaurants. The town began to expand, roads were traced, and the various districts were rapidly populated by people come down from the nearby mountains. The ground-floors were taken over by new commercial premises, such as pharmacies, dress-makers, newsagent-bookshops, and retailers of every description. The Sarrafian brothers took space in Bab Idriss. Trams clanked through the town and in 1892 the first film was shown in the café-theatre Zahret Souriya near Khan el-Tyan by the Burj. This place soon became the café Parisiana, much frequented by French officers under the Mandate.

The tangle of houses and narrow winding paved alleys within the walls of Beirut gave way to wider roads connecting the old town to more recent suburbs. Under the picks and shovels of demolition men working under the orders of the Wali of Beirut there appeared the remains of a Byzantine basilica, remains which now exist only immortalized in a photo by Sarrafian. Under the French Mandate, new buildings sprang up along the new avenues Foch and Allenby.

Postcards are faithful witnesses of what Lebanon was like in the twentieth century, without addition or touching up.

With the appearance of Beirut changing from day to day, purchasers of postcards no longer find shots showing what the town is really like, for the production of postcards has followed the evolution neither of the capital with all its changes, nor that of the coastal towns and the mountain resorts.

With the passing of time, postcards became used less and less for sending messages. Rather they became simple views without any correspondence, acquired for themselves to keep as a record. In fact, travelers began to purchase large numbers of postcards as simple souvenirs of their travels or as bright images to send to their relatives and friends, exotic scenes bathed in bright sunshine far from the grayness of Europe.

Beirut became a regional center for trade, an inevitable destination for missionaries and for journalists, for trippers and for famous authors. The construction of the Beirut-Damascus road, confided to Count Perthuis, the railway line laid down in 1893, the enlargement of the port of Beirut, together with journalism, printing and book publication, all promoted the development of these regions.

The rising number of travelers coming to the Near East created, moreover, new tourist routes and engendered an unprecedented demand for postal services, with postcards and photograph shops all encouraging the development of photography.

The influx of tourists meant an increasingly impressive demand for postcards. The first postcards from Lebanon, dating from the end of the nineteenth century, showed general views of Beirut and Baalbek, printed in medallions with the inscription Gruss aus, signifying souvenir from. Produced in Germany and Austria, they were sold in the bookshops of Beirut.

One of the first photographers to set up business in Lebanon was Félix Bonfils, who came in 1867 and whose work contributed considerably to the development of photographic art in the country. Other photographers followed him and started Business in Lebanon, such as Abraham Gargossian.

As from 1900, postcards came to be directly edited, printed and sold in the souvenir and antique shops of Beirut, such as those of Dimitri Tarazi and Dimitri Habis. The number of shops in Lebanon selling photographs grew steadily. The development of printing permitted the marketing of postcards costing less and available to the general public.

Among the 120 known editors, the Sarrafian brothers alone produced one fifth of the postcards printed in Lebanon between 1895 and 1930.

The Sarrafian brothers may be considered the giants of the postcard, so prolific and varied was their output and so avant-garde, precise and unique was their witness. Photo reporters of another era, the Sarrafian brothers had the genius to be in the right place at the right time, for example at the official opening of the station at the Port of Beirut, as well as the entry into service of the clock at the Main Saraglio (Government Office) in 1900 and of the Hamidieh fountain marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the accession to the throne of Sultan Hamid. They made a portrait of Sheikh Ibrahim el-Yazigi, founder of the review Al-Bayan.

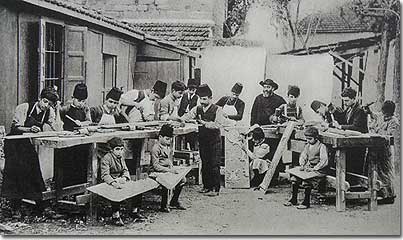

They were also present for the inauguration of the School of Arts and Crafts attended by the Wali and other notables of the city in 1907, and for the inauguration of the Ottoman Post near Khan Antoun Bey in 1908, also for the official opening of the Asfurieh psychiatric hospital. in 1900.

Their shots covered the liberation of the nationalist prisoners returning from exile in 1908, the bombardment of the city of Beirut by two warships of the Italian fleet and the wreck of the ship Aoun Allah off the port of Beirut in 1912. Later there were the poignant pictures of child victims of the famine of 1916 and ones of Beirut under snow in 1920.

Their inimitable series of daily life in Lebanon covered in turn with total authenticity all the crafts and scenes of town and country, often not without a certain gentle humor. At the As-Sour Square, later Ryad el-Solh Square, at the end of Ramadan it was the custom to celebrate with a traditional procession during which parents carried their circumcised children shoulder high. Finally, they preserved for immortality the old dwellings due for demolition with the widening of the streets of Beirut named Foch and Allenby.

The Sarrafian brothers were also the official photographers of the Syrian Protestant College, later known as the American University of Beirut, for which they published a series of postcards now exceedingly rare.

Among the souvenirs of our heritage we must not omit the Little Seraglio of the Place des Canons in Beirut. Built in 1884 according to the plans of Beshara Effendi, this little jewel of Ottoman architecture was destroyed in 1951 as a result of official indifference. It was replaced in 1952 by a modern construction, the Rivoli Building. During the war of 1975 this too was destroyed and archeological digging has brought to light the arches of the Little Seraglio basement.

Now one may well ask, could the historic monuments of the past not be reconstructed, following the example of certain European towns which survived the disasters of war? For example, in the city of Dresden, virtually destroyed by Allied aerial bombardment towards the end of the Second World War, the former buildings have been faithfully reconstructed so that a period of its history might not fall into oblivion. This was done in homage to its inhabitants and out of respect for their memory.

Of the cathedral of Dresden there remained only one section of wall, starting from which the edifice was restored in all its former splendor. The population of the city is proud of it.

So what if the Little Seraglio were to be restored? It needs only the Municipality to throw its efforts into rebuilding this historic architectural jewel and to give it a prominent place in the City Center. It should be recalled that Mr. Robert Debbas once asked me for all the postcards showing the Little Seraglio from every angle, for after having seen some postcards some months before his death Prime Minister Hariri had shown interest and even enthusiasm for its reconstruction.

Translated from the French by K.J. Mortimer

Beirut after the snow of 1920

Arts and Crafts School, run by the Jesuit Fathers

High Commissariat, Beirut

Inauguration of the School of Industry

Flight of Lebanese at the bombardment of the Port of Beirut by the Italians in 1912

Lebanese dying of hunger in 1914