The Lebanese Vision – A History of Painting by John Carswell

If one is to grasp the significance of this exhibition, with its kaleidoscopic diversity of style and content, it has first to be appreciated as a mirror of a very special society. Lebanon is a highly complex mixture of peoples and beliefs, held in delicate balance since the state attained its independence in 1943, and tragically rent asunder during the past decade; the forces which have destroyed Lebanon as it was, have proved more powerful than the dynamism born of this equilibrium. But this is to anticipate, and in order to understand the present artistic heritage it is necessary to look carefully into the past. Lebanon is unique in another sense, for it has never existed in a vacuum, and its relationship to Western society and the whole hinterland of the Middle East is the key to its special character.

Although the Phoenicians has contacts with the western Mediterranean, European consciousness of the Middle East began during the Roman Empire and crystallized with the Crusades. In the post-Crusading era, pilgrimage to the Holy Land continued and there was an increasing economic interest through trade. Later on, the area became of strategic importance because it lay between Europe and lands of greater commercial interest - Persia, India and the Far East. The Portuguese managed to leave the Middle East out of this equation by circumnavigating Africa, a manoeuvre later emulated by the Dutch, and then the colonial British. With the growth of the Ottoman empire and its expansion in the sixteenth century throughout Syria, Egypt and North Africa, the European powers had even less inclination to tussle with the new political entity unless, as in Eastern Europe, in self-defense. But trade was another matter, and with the caravan routes from Central Asia and the Middle East converging on the eastern Mediterranean, there were mechanisms for goods to flow freely in both directions. As the French traveler Tournefort put it, “all the Commodities of the East were made known in the West, and those of the West serve as new ornaments for the East”.

What were these goods? From the East came silk, porcelain, cotton, pepper and all sorts of spices. By the seventeenth century, the goods brought back from Europe made a formidable list; they included cloth, brocades, looking-glasses, Venetian glass, rosaries, false pearls, amber, paper, spectacles, watches, clocks, enamels, knives, buckles and needles. There was an increasing awareness of the products and inventions of European civilization in the three great empires of the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals. Oddly enough, it was a Christian minority, the immigrant Armenian merchants of Persia operating from the New Djulfa in Isfahan, who were largely instrumental in moving merchandise in both directions. With the monopoly of the silk trade from Persia, and with emissaries stationed all the way from Amsterdam to the Far East, they effectively controlled a large part of the international market.

No unnaturally, they were among the first to appreciate the novelty of Western painting, and in the seventeenth century commissioned a Dutch artist to decorate their newly founded churches in Isfahan, Shah Abbas I, their protector, was intrigued by this new style of painting, so different from the Persian tradition, and wall-paintings in his palace, the Chihil Sultan, are evidence of this. There are records of “John, a Dutchman” who was employed by the Italian traveler Pietro della Valle in the early seventeenth century and subsequently worked for Shah Abbas, who at one stage sent him back to Italy and France to seek other western painters to work for him. Persian artists were influenced by the western style, and the most famous of all, Muhammad Zaman, studied in Italy before returning to Persia and then finding employ at the Mughal court in India. Another channel of Western influence was the illustrated Bible, decorated with engravings, examples of which were brought by Christian missionaries.

In the Ottoman Empire the contacts were even more direct. Istanbul and Venice were in symbiotic relationship to each other through trade, and it was no coincidence that following an invitation to the Venetian Senate by Sultan Mehmed II, the painter Gentile Bellini spent more than a year in Istanbul, painting the famous portrait of the Sultan (now in the National Gallery in London) and generally exercising his art and his influence. Bellini presented Mehmed with an album of his father’s drawings, which still survives in the Louvre, and which contains many architectural drawings and other designs. It can be no coincidence that from about this period, Turkish miniature painting shows an awareness of everyday life and an attempt at verisimilitude which is quite novel, distancing itself from the poetic fantasy of the Persian miniature tradition.

To what extent this westernizing influence was felt in the Ottoman provinces is a matter of conjecture. In Lebanon, by the early seventeenth century Fakherddin II had brought the whole of the country under his rule; and tradition has it that as a result of his previous sojourn at the Medici court in Florence, he brought with him a whole Troup of Italian masons and craftsmen to build himself a palace in Beirut in the Italianate style. The emerging merchant class also added a new dimension. From the seventeenth century, throughout the Levant, a successful and affluent bourgeoisie introduced another kind of patronage. This is first of all to be seen in the kind of houses they built for themselves; in Aleppo, Damascus, Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre, Sidon and Jerusalem, mansions sprung up everywhere. With a wealth of carved stone decoration and pretty painted interiors, they were a natural setting for all sorts of ornament. Chinese and Japanese porcelain set on inlaid wooden tables, silk cushions and embroidered velvets, copper trays and silver utensils created an opulent setting for the merchants, provincial governors, local prince lings, landowners – and their womenfolk. Lebanon was no exception; the palace of the Shihabs at Bayt Al Dine in the mountains of the Chouf was a marvel of carved stone and cut ornament, in a style which can only be classified as Mamluk Revival.

Indeed, architecture always seems to have been one step ahead of the other arts when it came to innovation. In Lebanon, modern architecture was introduced and appreciated long before modern art was ever heard of. The classic example is the St George’s Hotel, designed by Antoine Tabet, himself a pupil of Auguste Perret, and built in 1929. This structure was among the first to use precast concrete components in its design, and right up until the time of its destruction in the seventies had a simple, contemporary elegance which set it apart from many more recent structures.

During the Ottoman Empire Lebanon was divided into different vilayets or administrative districts. Partly because of its inaccessibility, a range of precipitous mountains slashed by deep valleys and torrential rivers, deep in show at the summit and looking down on the narrow, fertile coast, Mount Lebanon has always retained a strong sense of individuality, a feudal and religious isolation. To the east, the dividing line of the mountains of Anti-Lebanon provides a kind of psychological barrier. In Lebanon, it is easy to stand back from the Mediterranean and view both eastern and western cultures with a somewhat Olympian detachment. What sort of art could flourish here?

It was an art of imagery, the creation of icons, an expression fundamentally religious but also with a strong hieratic flavor, The monasteries and churches are full of such icons, simple statements of religious faith which stylistically have their parallels worldwide at this period – in provincial Europe, all over South America and throughout Asia, indeed wherever Christianity had to be manifest in pictorial form. The Madonnas and Saints are declamatory rather than spiritual; those in the churches and monasteries of Lebanon are in direct lineal descent from the iconography of the ancient Near East. But they are not lacking in magic, and the supernatural is implicit in the penetrating, staring eyes. The same hypnotic vision can be seen in early Coptic paintings – and also in Fatimid art, as far west as Sicily. Technically, the paintings are inept; but that, in a way, is not the point; if you are making a statement for a visually unsophisticated audience, it is irrelevant. It is the statement itself which is important, and this is an attitude which has much bearing on the later development of painting in Lebanon.

In the nineteenth century, Lebanon knew a quiet prosperity which led to what might now consider its golden age, a period of awakening. The ports of Lebanon – Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre and Sidon – were the gateway to Syria and Palestine. For the first time, pilgrims were replaced by tourists, a new breed. The first hotel in the Middle East was created for them – the Grand Hotel Bassoul in Beirut (ironically, like the St Georges, also a victim of recent events), an investment by a successful dragoman Nicola Bassoul, who led tours to Syria and the Holy Land. Mulberries were cultivated in the hills above Jounieh, which became a successful centre for growing silkworms and the manufacture of silk. East-West trade continued to prosper, and along with economic development came a parallel development in education. The nineteenth century saw the transformation of the monastic system and the beginning of secular education. This was reinforced by the creation of two universities in Beirut for higher education, by the French and the Americans.

As far as Art is concerned, the religious paintings in the churches became even more accomplished, and the iconography expanded to include the clergy. Now Bishops and other prelates figured alongside the Madonnas and Saints. The style is more assured, and often the accoutrements more important than the subjects. Holy talismans, signs of office, religious and secular medals and insignia are more in focus than the person they adorn. In one memorable painting in the exhibition, the ecclesiastical regalia are so sharply defined that the face above fades into the shadows.

But there is another new and identifiable element. The nineteenth century led to an acceleration of European (and American) interest in what the land of the Bible actually looked like; this resulted in a swarm of topographical artists descending on the Middle East, to identify, quantify and pictorialize those sites most likely to interest a captive audience. Many of the artists, like David Roberts, had already exhausted the commercial potentiality of Europe – Gothic cathedrals in France and Belgium, and romantic Moorish monuments in Spain. Although only marginally interesting as far as the West was concerned, Lebanon did have Tyre and Sidon, Baalbek and the Cedars, and was so worth a detour. Some detoured more than others, and W.H. Bartlett left an exceptional record of many minor aspects of the country; Edward Lear also painted some sharply focused views. As for the Lebanese, they were singularly unaware that anyone was interested in what artists thought their country looked lie; except that this is not quite true.

Objectivity was not entirely the prerogative of painters. By the middle of the nineteenth century, photography had become a highly successful competitor with topographical painting, and Beirut had become the home of one of the most famous photographic families of them all. Felix Bonfils, his wife Lydie and son Adrien arrived in Beirut in 1877, and the family set up a studio in the middle of town. The Bonfils were indefatigable, and became the most prolific image-makers of the Middle East of all time. There was no corner of Syria, Palestine and Egypt, no topographical, religious, ethnic, social or incidental aspect of everyday life that was not grist to the Bonfils mill. Nowadays the academic interest of the photographs is obvious, but they were also highly charged emotive images as well. It is only during the past decade or so that this pictorial record of the Middle East in the late nineteenth century has been credited with the importance it merits. Besides Bonfils, there were others; in Beirut, Sarrafian and Saboungi were rival establishments, and in Jerusalem the American Colony produced its own series of photographs of the Holy Land. Also in Jerusalem, the Armenian Patriarch was himself a leading amateur photographer; and in Lebanon, the Maronite Bishop Emmanuel Phares El-Ferkh used his own photographs on his fund-raising lecture tours.

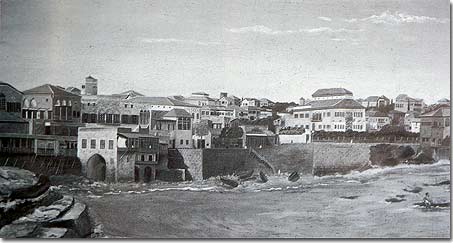

What was happening in the commercial world of photography was noticed by the painters, and a photographic way of looking at the world began to impinge on their own work. It is not too difficult to trace the impact of photography on the portraits of such painters as Daoud Corm and Khalil Saleeby. The photographic image helped to reinforce the potency of their paintings. Topographically, an extraordinary view of Beirut from the sea, each building delineated like the architecture in the background of some Italian primitive, can also be traced in origin to the inspiration of a monochrome Bonfils photograph. The painting, more than a meter wide, used to hang in the salon of the Grand Hotel Bassoul; it disappeared, alas, during the fighting and the gutting of the hotel, but a photograph of it survives.

Detail of a painting previously located in the Bassoul Hotel, Beirut. Anonymous, c. 1870

When one considers what was happening in France in the second half of the nineteenth century, it is odd that there appears to have been no influence of Impressionism on Lebanese painting. Although there were social and economic contacts, this did not lead to immediate cultural influence, as far as art is concerned. And yet this was not true for architecture, fashion, or language and literature. Why should the Lebanese have been unaware of pictorial developments in Europe? An explanation can perhaps be sought if we see the question in a wider context. In Russia and America this was a crucial moment, when artists decided they wanted to establish their own cultural and national identity and break away from the European tradition. In all of these countries, there was a Europeanizing academic tradition to be rejected. In Lebanon, with no academic tradition of this sort and no formal academy, there was nothing to renounce.

For a society to create and nurture an artistic tradition, there are two requisites; first, there must be the artists themselves; and second, there must be a public to support them. Artists seem to be a phenomenon which can turn up at any time or place on our planet; their existence is as predictable as an unfamiliar type of butterfly. An appreciative public is less easily created, unless – as in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Lebanon – the art is tied into some religious or otherwise acceptable background. The innate conservatism of the general public made it very difficult for artists to find a place in Lebanese society.

The artist, having decided on his vocation, is faced with some choices. If he is secure in his genius, he needs no further instruction, but this is so rare that it is as exceptional as genius itself. Most artists are aware that they need to pick up a trick or two to help to express themselves more effectively. This means art education, and in Lebanon initially the choice was either to study with someone more established, or to jump into the deep end and study abroad, mainly in Paris and Rome. Because France seemed to be the non plus ultra, Paris was ideal. Generations of young Lebanese painters beat the way to the capital, and absorbed ideas and styles which were more – or less – appropriate to them. But just as Paris was losing out to New York as the ultimate centre of the art world, more and more Lebanese painters set out for France. Nothing wrong in that, but they arrived after the stable door was open and all the horses had run away.

There were other places. A few discovered that you could learn about art in the United States, and those who did acquired a detachment which made it hard for them to fit into the Lebanese scene. In the States, nationality counted for nothing; in Lebanon, it was all. Perhaps one could find oneself in America and then return as a champion? Fine, but who was going to appreciate the novelty of this? Lebanese painters in Paris, after all, could play it both ways, one famous example returning every year to sell vastly to his Beirut public, in order to subsidize his life where he really wanted to be – in Paris.

What if you stayed at home? From 1937, you could study at the Lebanese Académie des Beaux-Arts, where there was the opportunity to acquire the necessary technical skills, and many of the artists in this exhibition studied there. From 1954, there was another alternative, when the American University of Beirut opened its Department of Fine Art. The brainchild of President Penrose, who was to die tragically shortly afterwards, a couple of American artists were imported from Chicago. Maryette Charlton and Georges Buehr both had close ties with the Art Institute of Chicago, and brought with them many of its pedagogical principles. First and foremost, the teachers had to be seen to be active, practicing and exhibiting artists in their own right. Second, no-one was to be excluded from the process of making art – anyone, and everyone, was encouraged to try. Third, art should be taught according to formal, not stylistic principles; this was the legacy of the Bauhaus. Perhaps the most innovatory contribution was a public program of lectures, demonstrations, and opportunities for anyone to try their skill. You got a sheet of paper, a piece of charcoal, or a paintbrush, a demonstration, and then you were on your own. These classes, called Art Seminars, had a dynamic impact; totally democratic, anyone could enroll. The first lady of Lebanon, Mme Zelpha Chamoun, became a fervent advocate. In the regular classroom, students at the University could take a class as viable elective. Some cynically, thought that it would be an easy way to pick up a credit or two; nothing could have been further from the truth. Perhaps one of the most interesting social innovations of these classes was the use of students as models for life classes. The administration probably never knew that for years the students posed for each other in the nude, with the utmost decorum.

If one is to grasp the significance of this exhibition, with its kaleidoscopic diversity of style and content, it has first to be appreciated as a mirror of a very special society. Lebanon is a highly complex mixture of peoples and beliefs, held in delicate balance since the state attained its independence in 1943, and tragically rent asunder during the past decade; the forces which have destroyed Lebanon as it was, have proved more powerful than the dynamism born of this equilibrium. But this is to anticipate, and in order to understand the present artistic heritage it is necessary to look carefully into the past. Lebanon is unique in another sense, for it has never existed in a vacuum, and its relationship to Western society and the whole hinterland of the Middle East is the key to its special character.

Although the Phoenicians has contacts with the western Mediterranean, European consciousness of the Middle East began during the Roman Empire and crystallized with the Crusades. In the post-Crusading era, pilgrimage to the Holy Land continued and there was an increasing economic interest through trade. Later on, the area became of strategic importance because it lay between Europe and lands of greater commercial interest - Persia, India and the Far East. The Portuguese managed to leave the Middle East out of this equation by circumnavigating Africa, a manoeuvre later emulated by the Dutch, and then the colonial British. With the growth of the Ottoman empire and its expansion in the sixteenth century throughout Syria, Egypt and North Africa, the European powers had even less inclination to tussle with the new political entity unless, as in Eastern Europe, in self-defense. But trade was another matter, and with the caravan routes from Central Asia and the Middle East converging on the eastern Mediterranean, there were mechanisms for goods to flow freely in both directions. As the French traveler Tournefort put it, “all the Commodities of the East were made known in the West, and those of the West serve as new ornaments for the East”.

What were these goods? From the East came silk, porcelain, cotton, pepper and all sorts of spices. By the seventeenth century, the goods brought back from Europe made a formidable list; they included cloth, brocades, looking-glasses, Venetian glass, rosaries, false pearls, amber, paper, spectacles, watches, clocks, enamels, knives, buckles and needles. There was an increasing awareness of the products and inventions of European civilization in the three great empires of the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals. Oddly enough, it was a Christian minority, the immigrant Armenian merchants of Persia operating from the New Djulfa in Isfahan, who were largely instrumental in moving merchandise in both directions. With the monopoly of the silk trade from Persia, and with emissaries stationed all the way from Amsterdam to the Far East, they effectively controlled a large part of the international market.

No unnaturally, they were among the first to appreciate the novelty of Western painting, and in the seventeenth century commissioned a Dutch artist to decorate their newly founded churches in Isfahan, Shah Abbas I, their protector, was intrigued by this new style of painting, so different from the Persian tradition, and wall-paintings in his palace, the Chihil Sultan, are evidence of this. There are records of “John, a Dutchman” who was employed by the Italian traveler Pietro della Valle in the early seventeenth century and subsequently worked for Shah Abbas, who at one stage sent him back to Italy and France to seek other western painters to work for him. Persian artists were influenced by the western style, and the most famous of all, Muhammad Zaman, studied in Italy before returning to Persia and then finding employ at the Mughal court in India. Another channel of Western influence was the illustrated Bible, decorated with engravings, examples of which were brought by Christian missionaries.

In the Ottoman Empire the contacts were even more direct. Istanbul and Venice were in symbiotic relationship to each other through trade, and it was no coincidence that following an invitation to the Venetian Senate by Sultan Mehmed II, the painter Gentile Bellini spent more than a year in Istanbul, painting the famous portrait of the Sultan (now in the National Gallery in London) and generally exercising his art and his influence. Bellini presented Mehmed with an album of his father’s drawings, which still survives in the Louvre, and which contains many architectural drawings and other designs. It can be no coincidence that from about this period, Turkish miniature painting shows an awareness of everyday life and an attempt at verisimilitude which is quite novel, distancing itself from the poetic fantasy of the Persian miniature tradition.

To what extent this westernizing influence was felt in the Ottoman provinces is a matter of conjecture. In Lebanon, by the early seventeenth century Fakherddin II had brought the whole of the country under his rule; and tradition has it that as a result of his previous sojourn at the Medici court in Florence, he brought with him a whole Troup of Italian masons and craftsmen to build himself a palace in Beirut in the Italianate style. The emerging merchant class also added a new dimension. From the seventeenth century, throughout the Levant, a successful and affluent bourgeoisie introduced another kind of patronage. This is first of all to be seen in the kind of houses they built for themselves; in Aleppo, Damascus, Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre, Sidon and Jerusalem, mansions sprung up everywhere. With a wealth of carved stone decoration and pretty painted interiors, they were a natural setting for all sorts of ornament. Chinese and Japanese porcelain set on inlaid wooden tables, silk cushions and embroidered velvets, copper trays and silver utensils created an opulent setting for the merchants, provincial governors, local prince lings, landowners – and their womenfolk. Lebanon was no exception; the palace of the Shihabs at Bayt Al Dine in the mountains of the Chouf was a marvel of carved stone and cut ornament, in a style which can only be classified as Mamluk Revival.

Indeed, architecture always seems to have been one step ahead of the other arts when it came to innovation. In Lebanon, modern architecture was introduced and appreciated long before modern art was ever heard of. The classic example is the St George’s Hotel, designed by Antoine Tabet, himself a pupil of Auguste Perret, and built in 1929. This structure was among the first to use precast concrete components in its design, and right up until the time of its destruction in the seventies had a simple, contemporary elegance which set it apart from many more recent structures.

During the Ottoman Empire Lebanon was divided into different vilayets or administrative districts. Partly because of its inaccessibility, a range of precipitous mountains slashed by deep valleys and torrential rivers, deep in show at the summit and looking down on the narrow, fertile coast, Mount Lebanon has always retained a strong sense of individuality, a feudal and religious isolation. To the east, the dividing line of the mountains of Anti-Lebanon provides a kind of psychological barrier. In Lebanon, it is easy to stand back from the Mediterranean and view both eastern and western cultures with a somewhat Olympian detachment. What sort of art could flourish here?

It was an art of imagery, the creation of icons, an expression fundamentally religious but also with a strong hieratic flavor, The monasteries and churches are full of such icons, simple statements of religious faith which stylistically have their parallels worldwide at this period – in provincial Europe, all over South America and throughout Asia, indeed wherever Christianity had to be manifest in pictorial form. The Madonnas and Saints are declamatory rather than spiritual; those in the churches and monasteries of Lebanon are in direct lineal descent from the iconography of the ancient Near East. But they are not lacking in magic, and the supernatural is implicit in the penetrating, staring eyes. The same hypnotic vision can be seen in early Coptic paintings – and also in Fatimid art, as far west as Sicily. Technically, the paintings are inept; but that, in a way, is not the point; if you are making a statement for a visually unsophisticated audience, it is irrelevant. It is the statement itself which is important, and this is an attitude which has much bearing on the later development of painting in Lebanon.

In the nineteenth century, Lebanon knew a quiet prosperity which led to what might now consider its golden age, a period of awakening. The ports of Lebanon – Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre and Sidon – were the gateway to Syria and Palestine. For the first time, pilgrims were replaced by tourists, a new breed. The first hotel in the Middle East was created for them – the Grand Hotel Bassoul in Beirut (ironically, like the St Georges, also a victim of recent events), an investment by a successful dragoman Nicola Bassoul, who led tours to Syria and the Holy Land. Mulberries were cultivated in the hills above Jounieh, which became a successful centre for growing silkworms and the manufacture of silk. East-West trade continued to prosper, and along with economic development came a parallel development in education. The nineteenth century saw the transformation of the monastic system and the beginning of secular education. This was reinforced by the creation of two universities in Beirut for higher education, by the French and the Americans.

As far as Art is concerned, the religious paintings in the churches became even more accomplished, and the iconography expanded to include the clergy. Now Bishops and other prelates figured alongside the Madonnas and Saints. The style is more assured, and often the accoutrements more important than the subjects. Holy talismans, signs of office, religious and secular medals and insignia are more in focus than the person they adorn. In one memorable painting in the exhibition, the ecclesiastical regalia are so sharply defined that the face above fades into the shadows.

But there is another new and identifiable element. The nineteenth century led to an acceleration of European (and American) interest in what the land of the Bible actually looked like; this resulted in a swarm of topographical artists descending on the Middle East, to identify, quantify and pictorialize those sites most likely to interest a captive audience. Many of the artists, like David Roberts, had already exhausted the commercial potentiality of Europe – Gothic cathedrals in France and Belgium, and romantic Moorish monuments in Spain. Although only marginally interesting as far as the West was concerned, Lebanon did have Tyre and Sidon, Baalbek and the Cedars, and was so worth a detour. Some detoured more than others, and W.H. Bartlett left an exceptional record of many minor aspects of the country; Edward Lear also painted some sharply focused views. As for the Lebanese, they were singularly unaware that anyone was interested in what artists thought their country looked lie; except that this is not quite true.

Objectivity was not entirely the prerogative of painters. By the middle of the nineteenth century, photography had become a highly successful competitor with topographical painting, and Beirut had become the home of one of the most famous photographic families of them all. Felix Bonfils, his wife Lydie and son Adrien arrived in Beirut in 1877, and the family set up a studio in the middle of town. The Bonfils were indefatigable, and became the most prolific image-makers of the Middle East of all time. There was no corner of Syria, Palestine and Egypt, no topographical, religious, ethnic, social or incidental aspect of everyday life that was not grist to the Bonfils mill. Nowadays the academic interest of the photographs is obvious, but they were also highly charged emotive images as well. It is only during the past decade or so that this pictorial record of the Middle East in the late nineteenth century has been credited with the importance it merits. Besides Bonfils, there were others; in Beirut, Sarrafian and Saboungi were rival establishments, and in Jerusalem the American Colony produced its own series of photographs of the Holy Land. Also in Jerusalem, the Armenian Patriarch was himself a leading amateur photographer; and in Lebanon, the Maronite Bishop Emmanuel Phares El-Ferkh used his own photographs on his fund-raising lecture tours.

What was happening in the commercial world of photography was noticed by the painters, and a photographic way of looking at the world began to impinge on their own work. It is not too difficult to trace the impact of photography on the portraits of such painters as Daoud Corm and Khalil Saleeby. The photographic image helped to reinforce the potency of their paintings. Topographically, an extraordinary view of Beirut from the sea, each building delineated like the architecture in the background of some Italian primitive, can also be traced in origin to the inspiration of a monochrome Bonfils photograph. The painting, more than a meter wide, used to hang in the salon of the Grand Hotel Bassoul; it disappeared, alas, during the fighting and the gutting of the hotel, but a photograph of it survives. (add the photo).

When one considers what was happening in France in the second half of the nineteenth century, it is odd that there appears to have been no influence of Impressionism on Lebanese painting. Although there were social and economic contacts, this did not lead to immediate cultural influence, as far as art is concerned. And yet this was not true for architecture, fashion, or language and literature. Why should the Lebanese have been unaware of pictorial developments in Europe? An explanation can perhaps be sought if we see the question in a wider context. In Russia and America this was a crucial moment, when artists decided they wanted to establish their own cultural and national identity and break away from the European tradition. In all of these countries, there was a Europeanizing academic tradition to be rejected. In Lebanon, with no academic tradition of this sort and no formal academy, there was nothing to renounce.

For a society to create and nurture an artistic tradition, there are two requisites; first, there must be the artists themselves; and second, there must be a public to support them. Artists seem to be a phenomenon which can turn up at any time or place on our planet; their existence is as predictable as an unfamiliar type of butterfly. An appreciative public is less easily created, unless – as in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Lebanon – the art is tied into some religious or otherwise acceptable background. The innate conservatism of the general public made it very difficult for artists to find a place in Lebanese society.

The artist, having decided on his vocation, is faced with some choices. If he is secure in his genius, he needs no further instruction, but this is so rare that it is as exceptional as genius itself. Most artists are aware that they need to pick up a trick or two to help to express themselves more effectively. This means art education, and in Lebanon initially the choice was either to study with someone more established, or to jump into the deep end and study abroad, mainly in Paris and Rome. Because France seemed to be the non plus ultra, Paris was ideal. Generations of young Lebanese painters beat the way to the capital, and absorbed ideas and styles which were more – or less – appropriate to them. But just as Paris was losing out to New York as the ultimate centre of the art world, more and more Lebanese painters set out for France. Nothing wrong in that, but they arrived after the stable door was open and all the horses had run away.

There were other places. A few discovered that you could learn about art in the United States, and those who did acquired a detachment which made it hard for them to fit into the Lebanese scene. In the States, nationality counted for nothing; in Lebanon, it was all. Perhaps one could find oneself in America and then return as a champion? Fine, but who was going to appreciate the novelty of this? Lebanese painters in Paris, after all, could play it both ways, one famous example returning every year to sell vastly to his Beirut public, in order to subsidize his life where he really wanted to be – in Paris.

What if you stayed at home? From 1937, you could study at the Lebanese Académie des Beaux-Arts, where there was the opportunity to acquire the necessary technical skills, and many of the artists in this exhibition studied there. From 1954, there was another alternative, when the American University of Beirut opened its Department of Fine Art. The brainchild of President Penrose, who was to die tragically shortly afterwards, a couple of American artists were imported from Chicago. Maryette Charlton and Georges Buehr both had close ties with the Art Institute of Chicago, and brought with them many of its pedagogical principles. First and foremost, the teachers had to be seen to be active, practicing and exhibiting artists in their own right. Second, no-one was to be excluded from the process of making art – anyone, and everyone, was encouraged to try. Third, art should be taught according to formal, not stylistic principles; this was the legacy of the Bauhaus. Perhaps the most innovatory contribution was a public program of lectures, demonstrations, and opportunities for anyone to try their skill. You got a sheet of paper, a piece of charcoal, or a paintbrush, a demonstration, and then you were on your own. These classes, called Art Seminars, had a dynamic impact; totally democratic, anyone could enroll. The first lady of Lebanon, Mme Zelpha Chamoun, became a fervent advocate. In the regular classroom, students at the University could take a class as viable elective. Some cynically, thought that it would be an easy way to pick up a credit or two; nothing could have been further from the truth. Perhaps one of the most interesting social innovations of these classes was the use of students as models for life classes. The administration probably never knew that for years the students posed for each other in the nude, with the utmost decorum